Lighting Magic

28 January 2016

16 June 2016

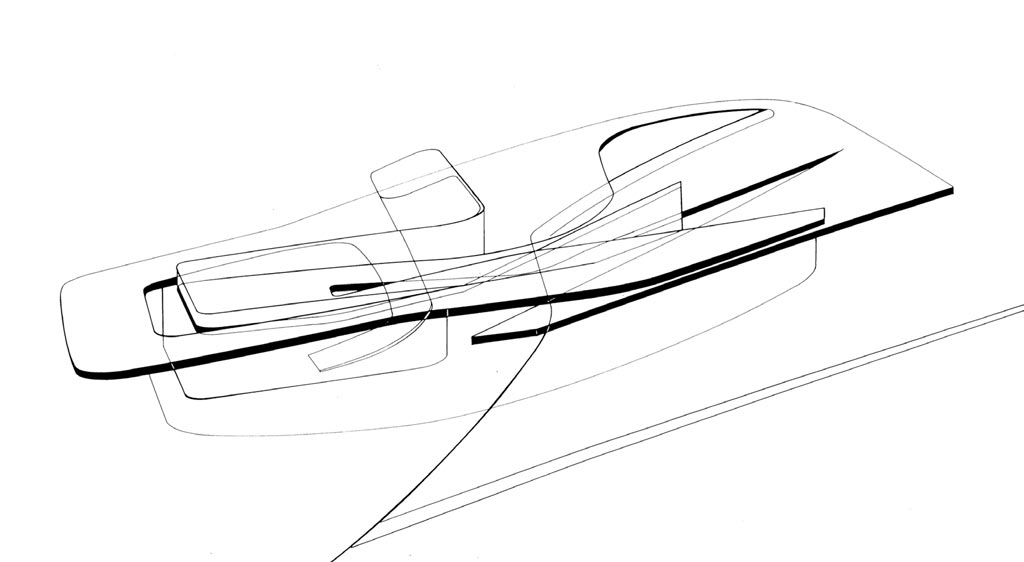

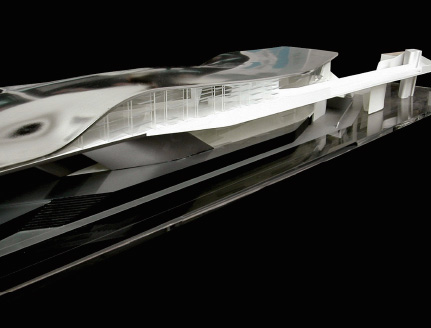

From the Suprematist revolution to Decontructivism, and on to the Parametric revolution, Zaha Hadid has changed our notions of space and its geometric perception. The term “archistar” seemed to fit her like a glove; no other has maintained a consistency of symbol and thought that places them in the firmament of great contemporary architects, as proven by her winning the prestigious Prizker Prize. One of her masterpieces is the MAXXI Museum in Rome, which won the Stirling Prize in 2010. We met with Margherita Guccione, the MAXXI Architectural Director, who had the honour of living the extraordinary adventure of building the museum alongside Zaha.

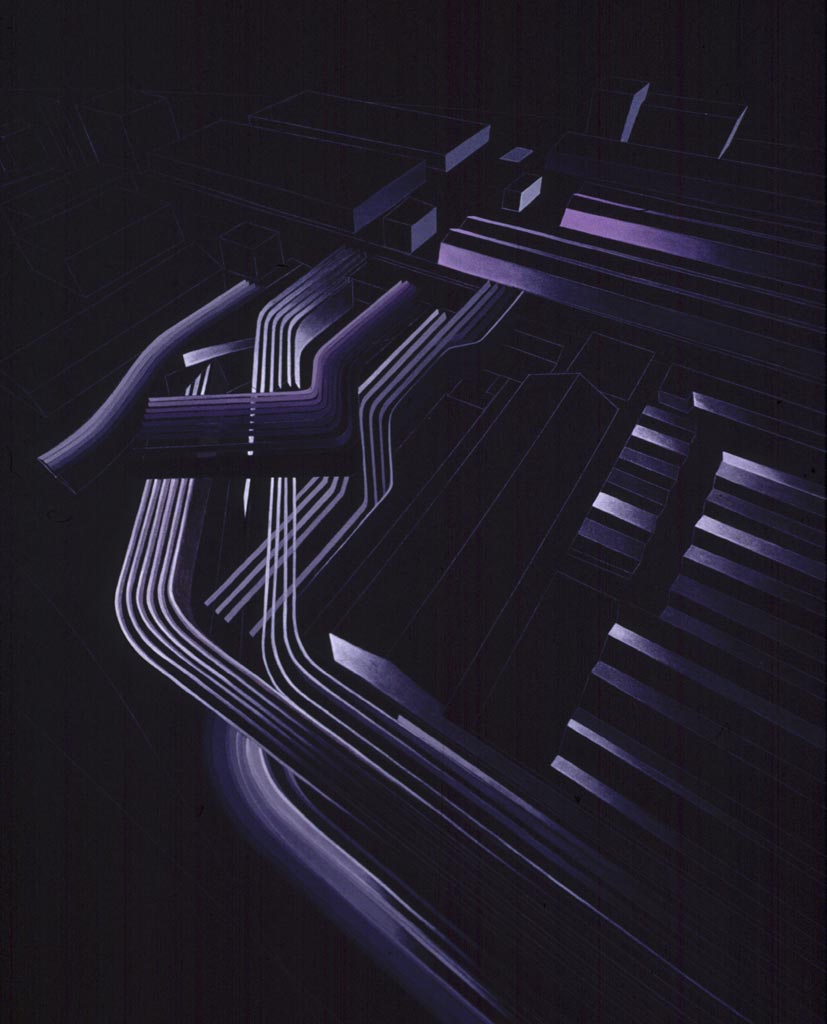

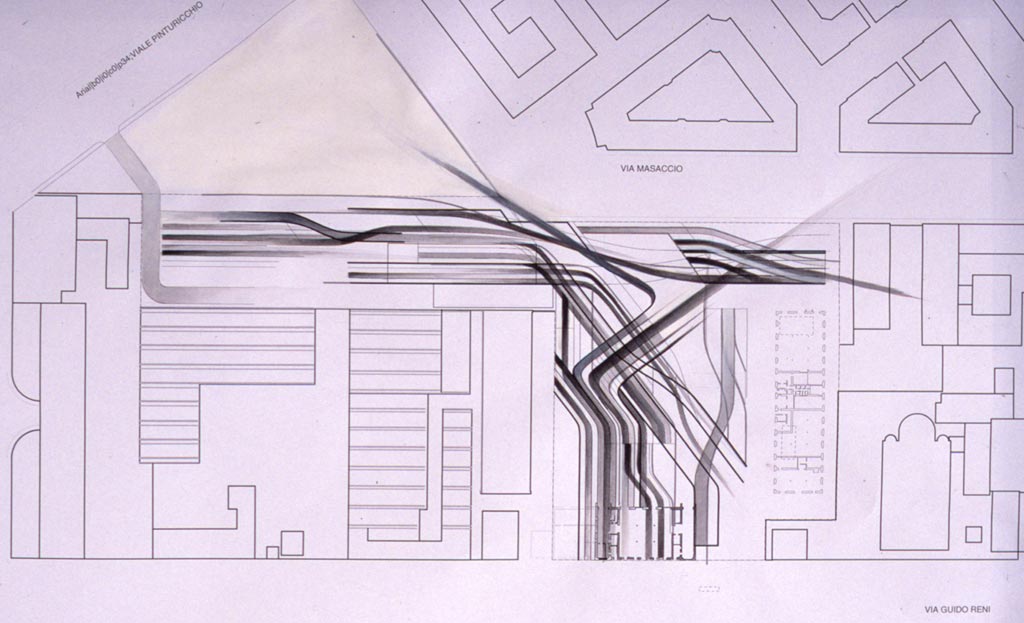

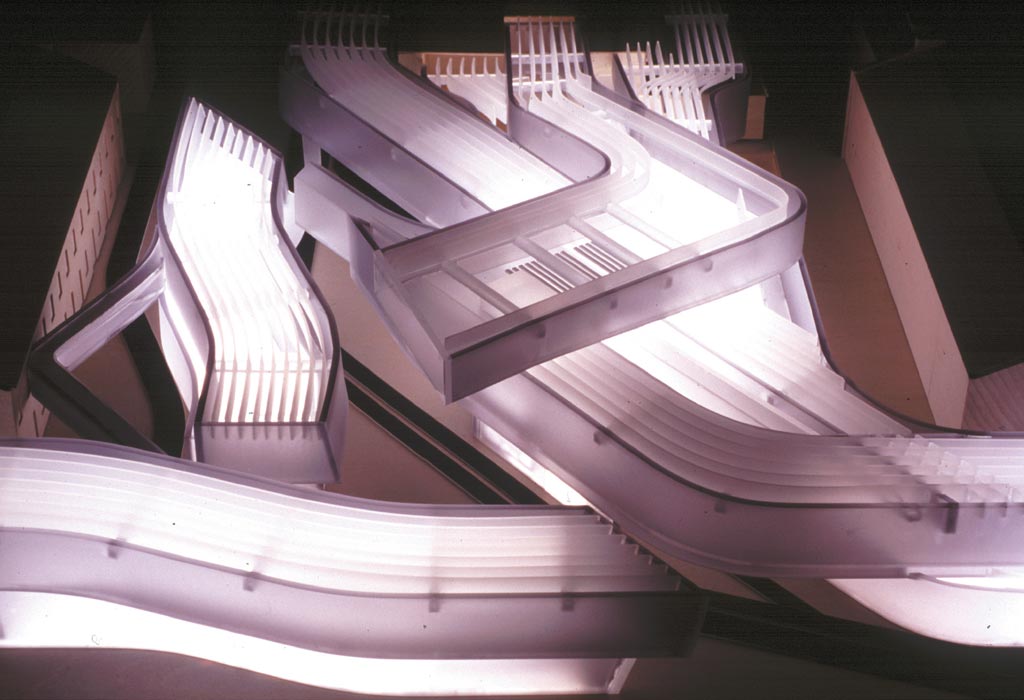

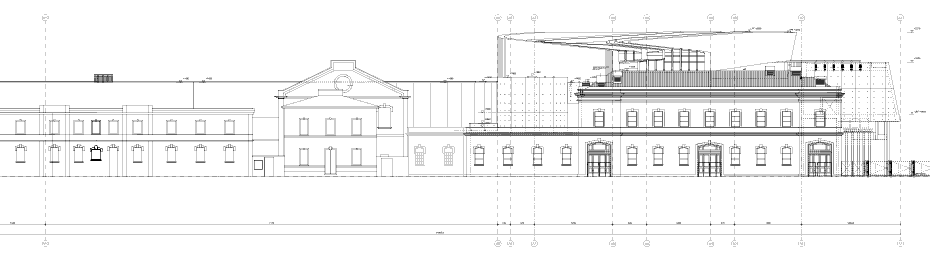

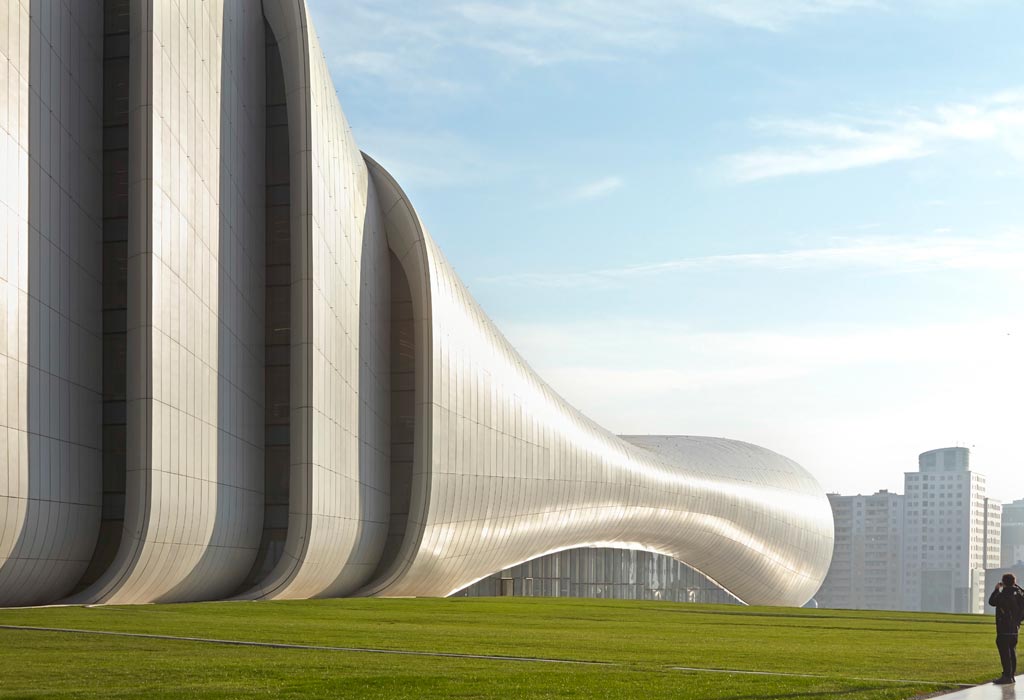

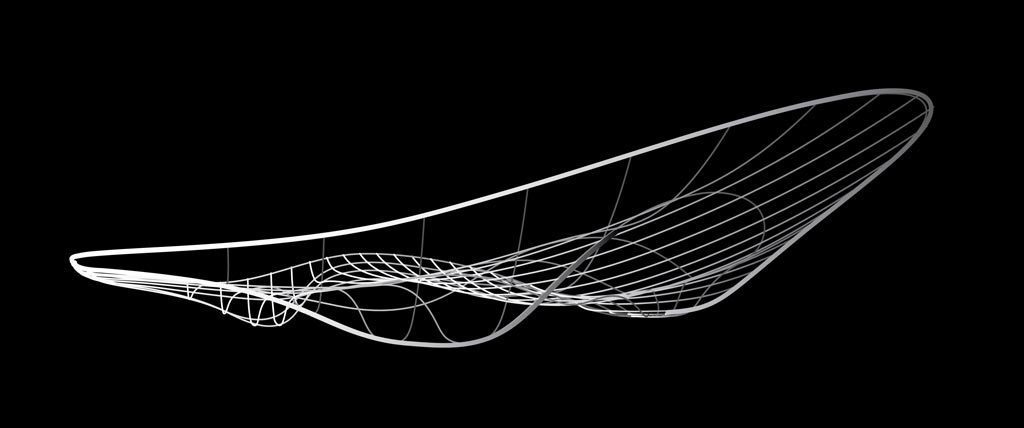

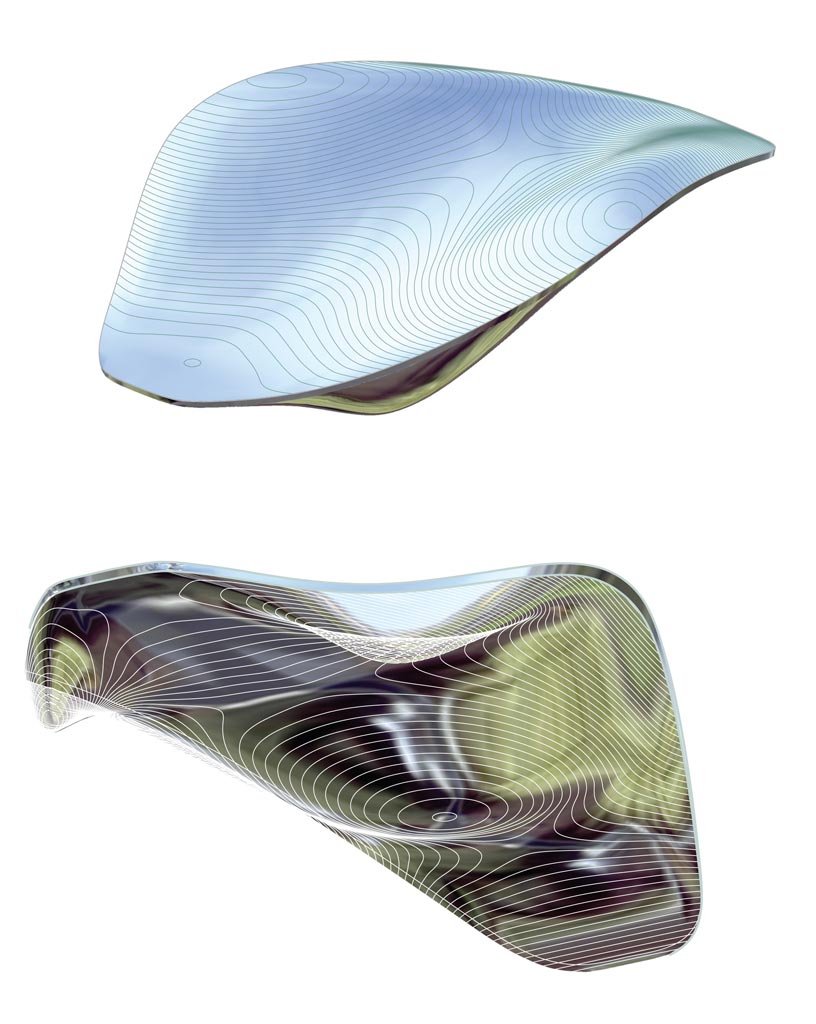

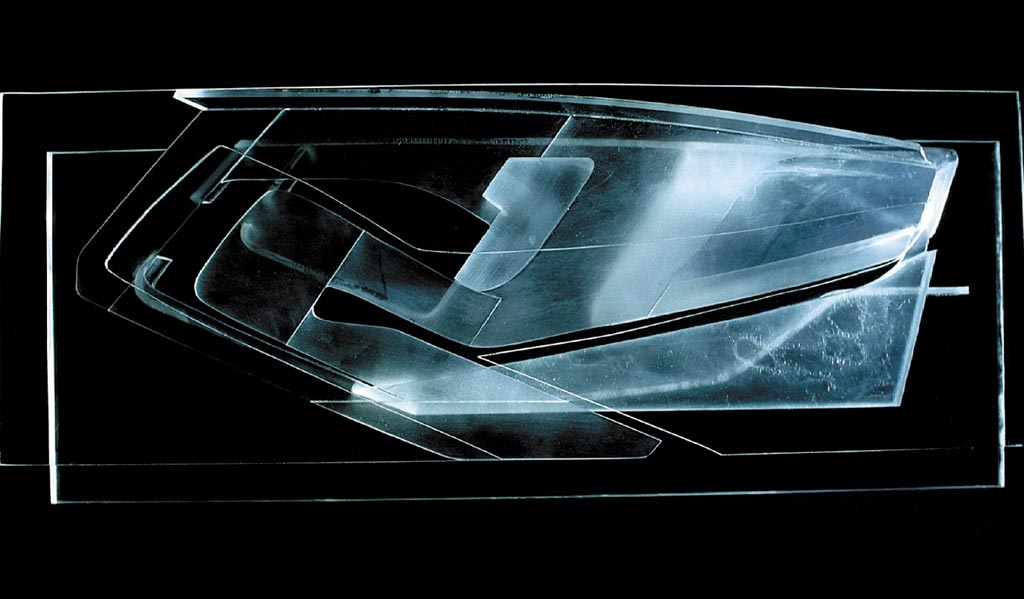

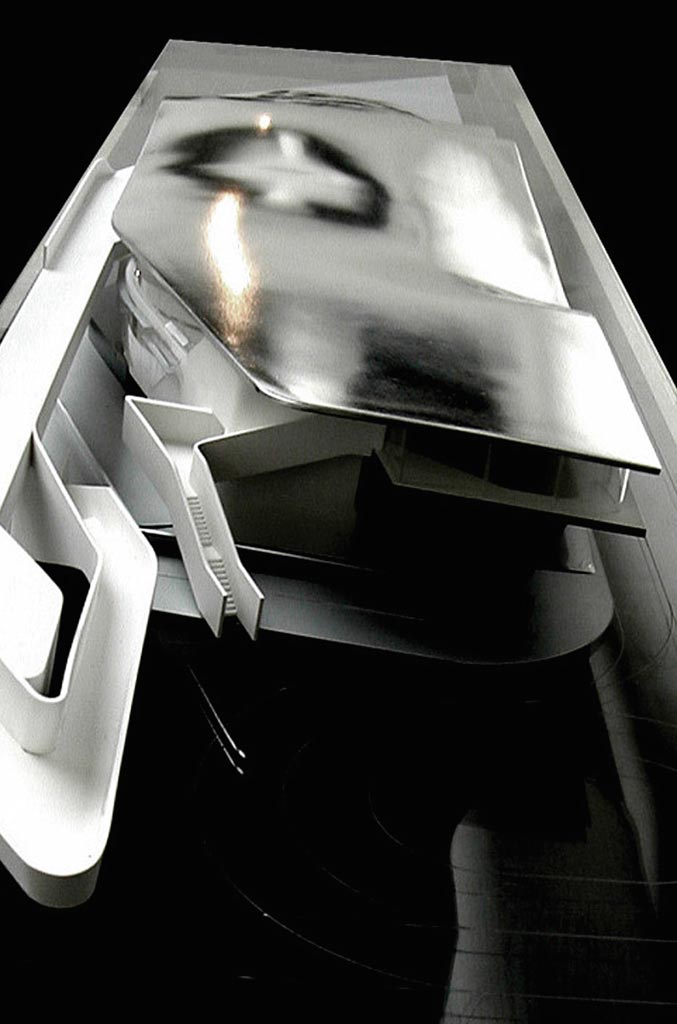

“MAXXI’s original designs were wonderful, hand-painted abstracts, narrating a very personal study that began with a reinterpretation of Malevich’s Suprematism. From there, the idea of a space working outside of Euclidean geometries was developed, resulting in a fluid, fleeting, dynamic vision, that of a genius, of a person with a diverse mental velocity”. In fact, MAXXI was designed before entering the parametric phase, much like London’s Aquatic Center, or the Baku Museum. In Rome, Hadid’s lack of early mathematic training was evident. Guccione continues, “From the beginning, it became clear that it was not necessary to design a building, but occupy a space. Her mathematical history drove her to speak of flow, of fields where an action’s energy could stream. She said, in fact, that, ‘Buildings are the frozen movements of those who will animate them’. She had the clear idea that architecture must give back public space to the city. It was not an aestheticized sculpture, as some have wrongly interpreted”. Just notice how the museum’s curve compliments the Tiber river bend, and converses with neighborhood life. What lessons has she left us? “Surely, that determination means integrity and consistency, even at the cost of losing relationships and stopping projects. But, as she said, ‘You cannot progress if you cannot deal with the unknown’”.

From the Suprematist revolution to Decontructivism, and on to the Parametric revolution, Zaha Hadid has changed our notions of space and its geometric perception. The term “archistar” seemed to fit her like a glove; no other has maintained a consistency of symbol and thought that places them in the firmament of great contemporary architects, as proven by her winning the prestigious Prizker Prize. One of her masterpieces is the MAXXI Museum in Rome, which won the Stirling Prize in 2010. We met with Margherita Guccione, the MAXXI Architectural Director, who had the honour of living the extraordinary adventure of building the museum alongside Zaha. “MAXXI’s original designs were wonderful, hand-painted abstracts, narrating a very personal study that began with a reinterpretation of Malevich’s Suprematism. From there, the idea of a space working outside of Euclidean geometries was developed, resulting in a fluid, fleeting, dynamic vision, that of a genius, of a person with a diverse mental velocity”. In fact, MAXXI was designed before entering the parametric phase, much like London’s Aquatic Center, or the Baku Museum. In Rome, Hadid’s lack of early mathematic training was evident. Guccione continues, “From the beginning, it became clear that it was not necessary to design a building, but occupy a space. Her mathematical history drove her to speak of flow, of fields where an action’s energy could stream. She said, in fact, that, ‘Buildings are the frozen movements of those who will animate them’. She had the clear idea that architecture must give back public space to the city. It was not an aestheticized sculpture, as some have wrongly interpreted”. Just notice how the museum’s curve compliments the Tiber river bend, and converses with neighborhood life. What lessons has she left us? “Surely, that determination means integrity and consistency, even at the cost of losing relationships and stopping projects. But, as she said, ‘You cannot progress if you cannot deal with the unknown’”.

The Moodboarders is a glance into the design world, which, in all of its facets, captures the extraordinary even within the routine. It is a measure of the times. It is an antenna sensitive enough to pick-up on budding trends, emerging talents and neglected aesthetics. Instead of essays, we use brief tales to tune into the rhythm of our world. We travelled for a year without stopping, and seeing as the memory of this journey has not faded, we have chosen to edit a printed copy. We eliminated anything episodic, ephemeral or fading, maintaining a variety of articles that flow, without losing the element of surprise, the events caught taking place, and the creations having just bloomed.